Who Was Adad (Hadad/Ishkur), the Mesopotamian Storm God?

Imagine standing on the plains of Mesopotamia as the horizon darkens and the air grows heavy. The first rumble shakes the earth, followed by flashes of lightning that split the sky. For the farmers who waited anxiously for rain, this was no ordinary storm—it was the presence of a god.To the people of the ancient Near East, that god was Adad, also called Hadad or Ishkur, the lord of thunder and storms. His voice was heard in the rolling thunder, his weapon seen in the lightning that struck the earth. More than a destroyer, he was also a giver: the rains he commanded brought crops to life and filled the rivers with water.

In every storm, Adad revealed his dual nature—both fierce and generous—reminding mortals that the forces of the sky could nurture or devastate, bless or punish, depending on the god’s will.

Origins and Early Role of Adad in Mesopotamian Mythology

Adad was born to Anu, the supreme sky God whose dominion stretched across the vast celestial realm. The identity of his mother remains shrouded in mystery, often left unnamed in the annals of mythology, hinting at a divine figure of considerable power and prestige.

Adad inherited a potent legacy, his very existence bound to the elemental forces of the sky. early years were a time of learning and growth for Adad, as he gradually honed his abilities to command the weather.

He was a God born from The Tempest, and his early years were a testament to the immense power he would wield in shaping the world. He learned to command the winds, summon rain, and orchestrate thunderstorms, skills that would later define his crucial role in both agriculture and the divine hierarchy.

His mastery over these elements was not merely about wielding power, but also about maintaining balance and nurturing life. As he matured, Adad's dominion over weather became more pronounced.

His mastery over these elements was not merely about wielding power, but also about maintaining balance and nurturing life. As he matured, Adad's dominion over weather became more pronounced.

He meticulously managed the climatic patterns, ensuring that the rains arrived timely for crops to grow and rivers to swell with life-sustaining waters. His reign over the weather patterns was not only a display of his might, but also a testament to his vital role in the natural order.

Adad's presence was synonymous with the sound of thunder rolling across the sky and the sight of lightning illuminating the heavens. Each storm under his command was both a spectacle of his power and a crucial ecological event, refreshing the earth and invigorating the landscapes.

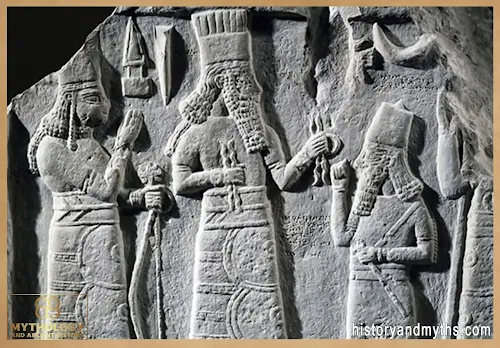

Adad, the Mesopotamian God of storms and rain, was depicted with distinct features in ancient art that highlighted his powerful and dynamic nature. This physicality reflected his active and forceful role in controlling the elements of weather.

Adad was associated with several symbols that reflected his powers and roles as the God of storms and rain. The Thunderbolt was one of the most significant symbols of Adad, representing his authority over Thunder and lightning.

Adad's familial connections, particularly regarding his parents, highlights the diverse and powerful influences that shape his role within Mesopotamian mythology. Anu, as the father of Adad, embodies the vastness and sovereignty of the sky, lending Adad an expansive realm of influence that stretches across the heavens.

In one of the most pivotal roles Adad played in Mesopotamian mythology, he appeared in the Atrahasis Epic, an ancient narrative that explores the origins of and solutions to human suffering.

|

| Shala, Adad |

| Deity | Region | Main Symbols | Key Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adad (Ishkur) | Mesopotamia | Thunderbolt, Bull | Storms, Rain, Fertility, Destruction |

| Hadad / Baal | Levant (Canaan/Syria) | Thunderbolt, Clouds | Storms, Fertility, “Rider on the Clouds” |

| Teshub | Hurrian–Anatolian | Bull, Storm-Chariot | Storm God, Weather Control |

| Zeus | Greece | Lightning Bolt, Eagle | Sky God, King of the Gods, Thunder |

Adad in Mesopotamian Art, Symbols, and Powers

Adad, the Mesopotamian God of storms and rain, was depicted with distinct features in ancient art that highlighted his powerful and dynamic nature. This physicality reflected his active and forceful role in controlling the elements of weather.

He was usually shown with a thick. Curly beard, a symbol commonly associated with virility and power in Mesopotamian iconography. This feature differentiated him from deities depicted with long, flowing beards, which were often symbols of wisdom and seniority.

Adad frequently wore a short tunic, which was practical and allowed for ease of movement, suitable for a deity associated with the active forces of nature, like storms and winds. Like many Mesopotamian gods, Adad was depicted wearing a horned cap or crown, signifying his divinity and sovereign status among the gods. The horns were a universal symbol of power and divine majesty in Mesopotamian culture.

Adad was often shown holding weapons or tools, such as a lightning fork or an axe. Which represented his ability to command the elements of storm and Thunder. These items not only symbolized his power, but also his role as a protector and warrior deity.

Adad was often shown holding weapons or tools, such as a lightning fork or an axe. Which represented his ability to command the elements of storm and Thunder. These items not only symbolized his power, but also his role as a protector and warrior deity.

Typically, Adad was depicted amidst the elements of his power, such as clouds, rain. And bolts of lightning, which surrounded him or emanated from his presence. These elements highlighted his role as the God of storms and reinforced his connection to the weather.

Adad's appearance aside, he was also known for his significant powers and roles that were crucial within Mesopotamian mythology.

Adad's primary duty was controlling the weather, being known as the God of storms, hurricanes, Thunder and rain. He determined the timing and amount of rain, summoning storms at will and bringing much-needed rain to water crops, fill rivers and sustain life, which was essential for agriculture.

Communities depended on his blessings for successful harvests and overall prosperity. Adad also had a role as a guardian.

Communities depended on his blessings for successful harvests and overall prosperity. Adad also had a role as a guardian.

He could unleash his power to defend his followers, using storms and lightning as weapons against enemies. This aspect of his character was often invoked in times of conflict, seeking his aid to cleanse or obliterate adversaries.

His mood could shift quickly, mirroring the sudden changes in weather from calm to turbulent. This aspect of his personality made him both feared and revered, as his favor could bring prosperity, but his displeasure could result in devastating storms.

His mood could shift quickly, mirroring the sudden changes in weather from calm to turbulent. This aspect of his personality made him both feared and revered, as his favor could bring prosperity, but his displeasure could result in devastating storms.

Adad was fundamentally A protective deity. Was invoked in times of war and conflict, where he would be asked to unleash his storms against enemies.

|

| Adad storm god |

Symbols of Adad: Thunderbolt, Bull, and Storm Imagery

Adad was associated with several symbols that reflected his powers and roles as the God of storms and rain. The Thunderbolt was one of the most significant symbols of Adad, representing his authority over Thunder and lightning.

This symbol was often depicted in art and iconography, illustrating his power to both nurture the earth with rain. And wield destructive forces. The bull was another powerful symbol associated with Adad, embodying strength, fertility, and the rumbling of Thunder. The bull's robust and forceful nature mirrored Adad's control over storms and his vigorous, life-giving rains.

Sometimes Adad was associated with the lion-dragon, a mythical creature that combined aspects of both a lion and a dragon. This hybrid creature symbolized his ferocity. And his role as a guardian deity capable of great protection and wrath. Adad was frequently depicted wielding an axe or a Mace, tools that symbolized his ability to strike with force and precision, much like a Thunderbolt.

These weapons also represented his warrior aspects, reinforcing his role as a protector deity who could unleash devastating power against his enemies.

|

| Adad atop the Bull |

⚡ Infographic: Adad (Hadad/Ishkur) ⚡

- Identity: Mesopotamian storm and thunder god, also called Hadad (West Semitic) and Ishkur (Sumerian).

- Symbols: Thunderbolt, bull, storm clouds — embodying strength and fertility.

- Dual Nature: Bringer of rain and fertility, yet also destructive through floods and storms.

- Consort: Shala, goddess of grain and abundance, reinforcing Adad’s link to fertility.

- Key Myths: Atrahasis Flood, Epic of Anzu, Epic of Erra — highlighting his power and unpredictability.

- Worship: Temples in Babylon, Assur, Nineveh; rituals invoking storms for crops and divine justice.

© historyandmyths.com — Educational use

Family of Adad: Parents, Consort Shala, and Children

Adad's familial connections, particularly regarding his parents, highlights the diverse and powerful influences that shape his role within Mesopotamian mythology. Anu, as the father of Adad, embodies the vastness and sovereignty of the sky, lending Adad an expansive realm of influence that stretches across the heavens.

Anu's rulership over the uppermost aspects of the cosmos imparts to Adad the authority to govern the skies and command the weather patterns that impact the Earth below. His mother, however, is not as clear-cut, with several goddesses potentially fitting that role.

Antu, potentially Adad's mother, compliments Anu's celestial authority, with her role often linked to the ethereal aspects of the sky if Antu is considered Adad's mother. He, if seen as Adad's mother, represents the Earth itself, grounding Adad's celestial powers with a direct connection to the land and its fertility.

Whichever narrative you choose to accept, the fact remains that Adad's diverse parentage contributes distinct qualities to Adad's divine persona, crafting him as a complex figure whose powers are essential for the maintenance of life and order on Earth.

Whichever narrative you choose to accept, the fact remains that Adad's diverse parentage contributes distinct qualities to Adad's divine persona, crafting him as a complex figure whose powers are essential for the maintenance of life and order on Earth.

Whether through celestial dominion, earthy connection, or specific atmospheric control, a dad's parentage equips him to play a crucial role in Mesopotamian mythology, overseeing the natural forces that both nurture and challenge human existence.

But it was not only his parents, but also his beloved consort who played vital roles in the shaping of the world in Mesopotamian myths. Shala is a goddess in Mesopotamian mythology.

Who is primarily associated with grain and the fertility of the Earth, but she also has connections to weather phenomena complement. Her role in agriculture as a deity whose domains are crucial for the sustenance and prosperity of society, Shala is revered as a vital figure in the Pantheon.

Who is primarily associated with grain and the fertility of the Earth, but she also has connections to weather phenomena complement. Her role in agriculture as a deity whose domains are crucial for the sustenance and prosperity of society, Shala is revered as a vital figure in the Pantheon.

Shala is often depicted as a nurturing figure, sometimes shown holding sheaves of grain or a double-sided Mace that could symbolize fertility and the duality of nature's bounty and wrath. Her iconography may also include elements that symbolize rain and storms, tying her activities directly to her husband. Shala is married to Adad, making them a divine pair whose functions are deeply intertwined.

In addition to his consort, Adad is said to have had multiple offspring, each holding significant roles within Mesopotamian mythology. However, some are only mentioned in passing, with very little information known about them. Šubanuna, Namašmaš and Menunesi.

In addition to his consort, Adad is said to have had multiple offspring, each holding significant roles within Mesopotamian mythology. However, some are only mentioned in passing, with very little information known about them. Šubanuna, Namašmaš and Menunesi.

Are three lesser-known deities among the children of Adad. There is limited specific information about these gods, but like many of Adad's offspring, their attributes might be connected to natural phenomena, possibly relating to specific weather patterns or agricultural aspects influenced by storms. Misharu is primarily associated with justice and law.

His name itself signifies justice or righteousness. Pointing to his role as a divine embodiment of fairness and legal integrity, Misharu's presence in Mesopotamian mythology underscores the cultural importance of law and order, reflecting the societal emphasis on maintaining balance and ethical conduct.

His name itself signifies justice or righteousness. Pointing to his role as a divine embodiment of fairness and legal integrity, Misharu's presence in Mesopotamian mythology underscores the cultural importance of law and order, reflecting the societal emphasis on maintaining balance and ethical conduct.

As a son of Adad and Shala, Misharu inherits aspects related to the natural order and its impact on human life. Usur-amassu is another deity associated with justice, though specific details about his functions are less clear compared to more prominent gods. His name suggests a connection to power and authority, implying a role that may involve the enforcement or administration of divine and earthly laws.

Like Misharu, Usur-amassu symbolizes the importance of legal and moral order in Mesopotamian culture. Usur-amassu's relationship with his parents, Adad and Shala, enhances his association with justice through the lens of natural and agricultural order.

Adad's mastery over storms, potentially destructive yet vital for life, can be paralleled with the sometimes harsh but necessary decisions in legal judgments. Jibil, often associated with fire and sometimes with forging and smithery, is an interesting figure and is sometimes attributed as the child of Adad.

|

| Shala and Adad |

Adad’s Role in the Atrahasis Epic and Flood Myth

In one of the most pivotal roles Adad played in Mesopotamian mythology, he appeared in the Atrahasis Epic, an ancient narrative that explores the origins of and solutions to human suffering.

The story unfolds with the gods, disturbed by the clamor of the human population, deciding that the earth needed a cleansing. Enlil, seeking to restore divine peace, proposed a flood to reduce humanity's numbers. Despite Enki's protests against such an act, Enlil sought to proceed with this plan.

Here, Adad was tasked with the execution of this grim decree, harnessing his most fearsome powers alongside Enlil. Adad's role was crucial in chilling. He gathered dark clouds over the horizon, each one swollen with the promise of rain.

Here, Adad was tasked with the execution of this grim decree, harnessing his most fearsome powers alongside Enlil. Adad's role was crucial in chilling. He gathered dark clouds over the horizon, each one swollen with the promise of rain.

What began as a gentle drizzle soon turned into a torrential downpour, unlike any seen before. For days and nights, Adad's storms raged, covering the earth with water, washing away entire communities, civilizations, and reshaping the landscape. His floods were not merely natural phenomena.

They were divine retribution, meant to silence the noise of humanity that had disrupted the gods' tranquility. As the waters receded, the gravity of Adad's actions became apparent. Adad's reigns had ended lives. But also offered a fresh start, a poignant reminder of his dual nature as both destroyer and life giver.

Adad in the Epic of Anzu: Storms Against Chaos

In the tumultuous saga of the Epic of Anzu, Adad stands as a guardian of divine order against chaos. The monstrous Anzu, a creature that was a blend of a bird and lion, had stolen the tablet of destinies from Enlil, usurping control over the fates from the gods themselves.This act of defiance threw the heavens into disarray. And Adad, along with the Divine Assembly of Gods, was summoned to address this grave threat. As the gods convened, the urgency of reclaiming the stolen tablet was palpable. Without it, the ordained order of the world was at risk. Adad, with his command over the storms, was a crucial ally in this cosmic battle.

His ability to wield the weather as a weapon made him uniquely suited to confront Anzu when the time came to face Anzu. Adad unleashed his full might.

His ability to wield the weather as a weapon made him uniquely suited to confront Anzu when the time came to face Anzu. Adad unleashed his full might.

The skies darkened, Thunder rolled like the drums of war, and lightning flashed as if heralding the god's wrath. His storms were not just meteorological events, but strategic assaults that disoriented Anzu, weakening the monstrous usurper and allowing the godly forces to gain the upper hand. However, all this was for naught.

The Anzu was simply too powerful for Adad to defeat. Enki, the God of Wisdom, then suggests that Ninurta, the warrior God, be sent after the Anzu. Despite his initial struggles, Ninurta is victorious in the end, slaying the Anzu and retrieving the Tablets of Destinies. Though Adad did not defeat the beast, his role was pivotal. His storms had helped to contain the chaos unleashed by Anzu, ensuring that order was restored.

In a narrative that explores themes of destruction and renewal, the Epic of Erra highlights Adad's alliance with Erra, or Nergal, the god of plague and war.

Adad’s Role in the Epic of Erra: Destruction and Renewal

In a narrative that explores themes of destruction and renewal, the Epic of Erra highlights Adad's alliance with Erra, or Nergal, the god of plague and war.

This story paints a picture of divine intervention designed to rejuvenate the Earth through cycles of devastation and rebirth. In this tale, Erra felt that the Earth had become complacent and that the gods were being forgotten by humanity. To remind the world of their power and to cleanse it of its ills, Erra proposed a plan of widespread destruction.

Adad, understanding the necessity of renewal, joined forces with Erra, aligning his stormy powers with Erra's warlike fury. Adad summoned his most formidable storms, each one meticulously timed to coincide with Erra's assaults.

Together, they swept across the land, toppling civilizations, erasing the old, and making space for new growth. Their actions were harsh but seen as necessary within the context of divine will, purging the world of stagnation and decay.

Together, they swept across the land, toppling civilizations, erasing the old, and making space for new growth. Their actions were harsh but seen as necessary within the context of divine will, purging the world of stagnation and decay.

After the storms and battles had passed, the earth was left bare, but not barren from the destruction. New life began to sprout, and humanity was given a chance to rebuild, wiser and more aware of the god's might. Adad's role in this process was dual.

His storms not only destroyed, but also watered the new seeds of life, illustrating his complex nature as both a destroyer and a life giver. These chapters in the mythology of Adad highlight his integral role, not just as a deity controlling the weather, but as a pivotal figure in maintaining the cosmic balance through the application of his powers. Whether in battle against chaos or in alignment with divine schemes of destruction and renewal.

Adad's critical role in agriculture and his control over the potentially destructive forces of nature made him an essential deity in the Mesopotamian pantheon, revered across the ancient Near East.

Worship of Adad in Mesopotamia: Temples, Rituals, and Devotion

Adad's critical role in agriculture and his control over the potentially destructive forces of nature made him an essential deity in the Mesopotamian pantheon, revered across the ancient Near East.

Farmers who depended directly on the rains for their livelihood held Adad in particularly high regard. They saw his moods reflected in the weather patterns.

And planned their planting and harvesting cycles around his temperaments. The most intense periods of devotion to Adad occurred just before and during the planting season.

Adad, the storm God of Mesopotamia, embodies the duality of nature, both its life-giving generosity and its unforgiving fury. His legacy and mythology highlight the dependence of ancient civilizations on the natural elements and the divine figures believed to control them.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Adad in Near Eastern Mythology

Adad, the storm God of Mesopotamia, embodies the duality of nature, both its life-giving generosity and its unforgiving fury. His legacy and mythology highlight the dependence of ancient civilizations on the natural elements and the divine figures believed to control them.

As the Thunder of Adad's legacy fades into the whispers of ancient texts, his story remains a powerful reminder of humanity's eternal dance with nature and the divine forces we imagine govern it.

Key Takeaways

- Adad (also called Hadad/Ishkur) is the Mesopotamian storm and thunder god tied to life-giving rain and destructive tempests.

- His core symbols are the thunderbolt and the bull; he is often paired with the grain goddess Shala.

- He shows a dual nature: bringer of fertility and harvests, yet also a source of floods and devastation.

- In major narratives, he plays a role in the Flood (Atrahasis) and appears in contexts like the Anzu and Erra epics.

- Cross-culturally he parallels West-Semitic Hadad/Baal and, functionally, weather gods like Teshub and Zeus.

- Worship centered across Mesopotamian cities, with rites seeking timely rains and divine justice through the storm.

Frequently Asked Questions about Adad (Hadad/Ishkur)

1) Who was Adad in Mesopotamian religion?

Adad—also known as Hadad (West Semitic) and Ishkur (Sumerian)—was the storm and thunder god whose rains sustained agriculture and whose tempests could destroy.

2) What symbols represent Adad?

The thunderbolt and the bull are his prime emblems; storm clouds and the lightning fork often accompany him in art.

3) Who was Adad’s consort?

Shala, a grain and fertility goddess, is commonly paired with Adad, underscoring his connection to crops and seasonal abundance.

4) Is Adad the same as Hadad/Baal?

In West-Semitic traditions, Hadad/Baal closely parallels Adad; many attributes and functions overlap across regions.

5) What is Adad’s role in the Mesopotamian Flood story?

In the Atrahasis tradition, Adad unleashes the deluge as part of a divine decree, showing the destructive side of his storms.

6) Where and why was Adad worshipped?

Across Mesopotamian cities, devotees sought his favor for timely rains, fertility, and sometimes justice wielded through the storm.

Sources

- Black, Jeremy, and Anthony Green. Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. London: British Museum Press, 1992.

- Dalley, Stephanie. Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Revised edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Lambert, W. G. Babylonian Creation Myths. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2013.

- Bottéro, Jean. Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia. Translated by Teresa Lavender Fagan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- Hallo, William W., and J. J. A. van Dijk. The Exaltation of Inanna. Yale Near Eastern Researches, 1968. (for comparative storm-god context)

- Frayne, Douglas R. Old Babylonian Period (2003–1595 BC). RIME 4. University of Toronto Press, 1990. (inscriptions mentioning Adad)

- Kaufmann, Yehezkel. The Religion of Israel: From Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile. Translated by Moshe Greenberg. University of Chicago Press, 1960. (background on Hadad/Baal and West-Semitic parallels)

Written by H. Moses — All rights reserved © Mythology and History